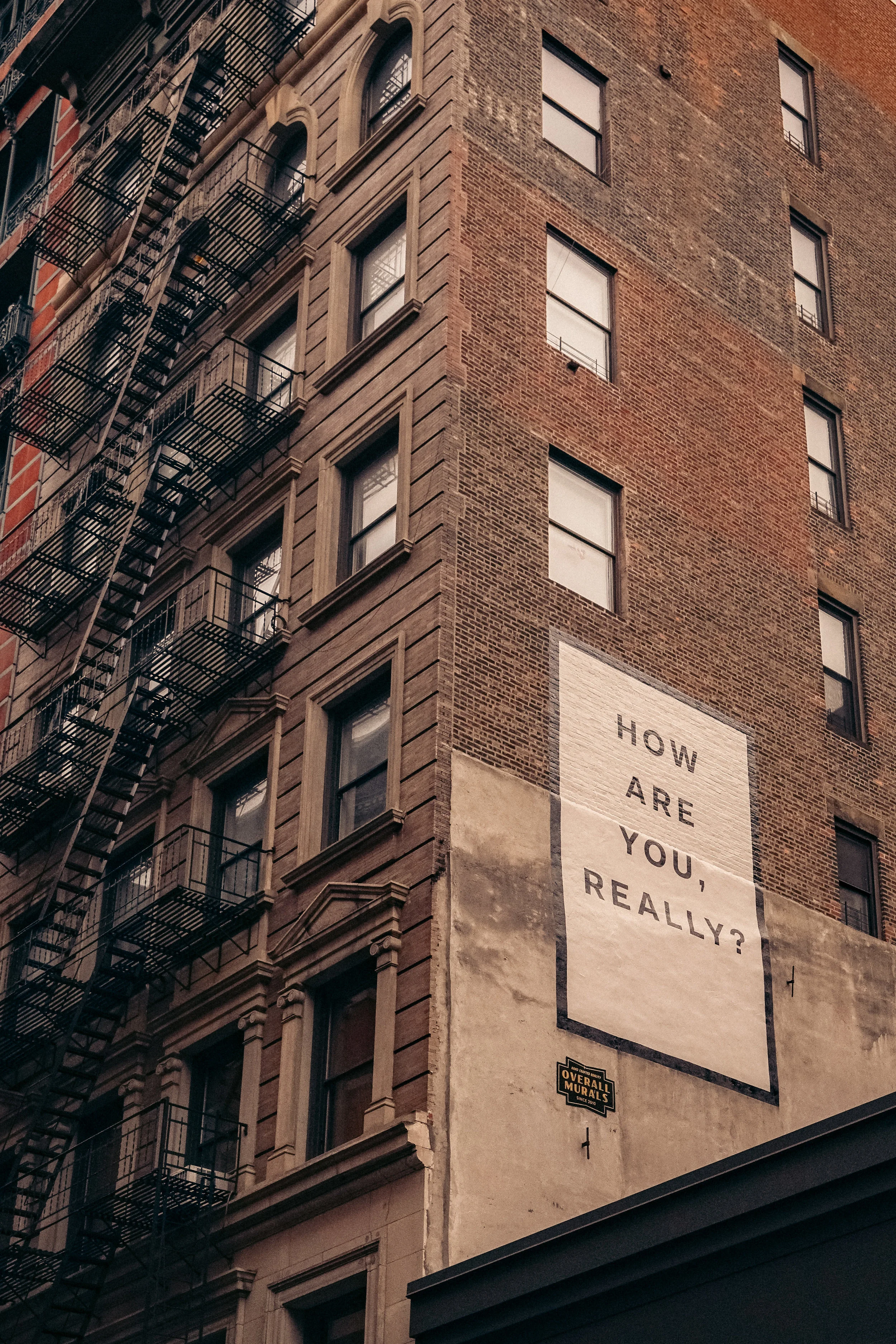

What if we treated mental health like health?

“Through this application, the Board of Bar Examiners makes inquiry about recent mental and physical health and chemical dependency matters. This information, along with all other information, is treated confidentially by the Board. The Board's purpose in making such inquiries is to determine the current fitness of an applicant to practice law. The mere fact of treatment for medical conditions or impairments or chemical dependencies is never, in itself, a basis on which an applicant is ordinarily denied admission, and the Board routinely certifies for admission individuals who have demonstrated personal responsibility and maturity in dealing with these issues. The Board supports and encourages applicants who may benefit from assistance to seek it. The Board has, on occasion, denied certification to applicants whose ability to function was impaired in a manner substantial enough to affect the applicant's ability to practice law at the time the licensing decision was made.

The Board usually does not seek information about therapy that is fairly characterized as stress counseling, domestic counseling, grief counseling, or counseling for eating or sleeping disorders, as these are generally not viewed as germane to the issue of whether an applicant is qualified to practice law.”

—Wisconsin application questionnaire, page 11

When I was in law school and applying for bar membership, there were a number of character and fitness questions seeking information about substance abuse and mental health. I (somewhat shockingly, I’m a pack rat) don’t have the questionnaire anymore so I don’t remember the exact questions, but I do remember the Board of Bar Examiners asking if applicants had sought counseling or other mental health treatment. I do not recall whether the above caveats were present (though I believe we were told we did not need to disclose stress/domestic/eating disorder counseling). I remember that it felt intrusive and stigmatizing, even though I have been fortunate and I didn’t have much to disclose.

I do remember very distinctly the question about drugs: “Have you ever used marijuana, cocaine, or other drugs of abuse?” If that’s not exact, it’s darn close. “Ever” was definitely in there.

There are four kinds of people answering that question—(1) people like my mom, who says she’s never even had a full glass of wine and I believe it and there are very few of them; (2) people who disclosed the occasional joint, or that one hit of acid at the Folk ‘n Blues Festival freshman year not that that very very specific example means anything, and maybe got a follow-up inquiry but at the very least sweated until the certification was complete; (3) people who disclosed arrests, dependency, or other major issues and certainly got a follow-up inquiry; and (4) damned liars, who skated because how else would the BBE know?.

Anyway, I think the BBE saw the limits of that question and killed it a year or two later. Now, they ask only about whether substance use has led to problems, so people in category #3 get some extra scrutiny and the people who are in #2 or who would be in #2 if they weren’t damned liars don’t. That’s fair.

The mental health questions have been revised in a similar fashion, and the prefatory paragraph I’ve pasted above purports to provide reassurance to applicants that their seeking help when they need help won’t be held against them. And after a decade in practice, and several years working with lawyers, I have seen many examples of students with substance use disorders or mental health challenges go on to thrive in practice.

Still, there’s a genuine worry among students, both (anecdotally) in Wisconsin and (per a study) nationally that seeking help (which lawyers, by their/our stubborn nature, are reluctant to do as it is) will keep them from becoming lawyers. So they slog through without help. They wouldn’t want the BBE (or anyone else) digging through their progress notes even if ultimately what’s in there won’t keep them out of the bar—and would you? Would you be candid with a therapist if you knew that you would need to waive your right to privacy to get a job?

A lawyer who is taking medication and regularly seeing a therapist for a serious mental health condition is going to be a better lawyer than one who needs help but tries to go it alone and succeeds “good enough,” for now, even though the former will likely be subject to far greater scrutiny than the latter. We shouldn’t throw up barriers to seeking treatment for mental health or substance use conditions. We should encourage it.

I was heartened to hear what happened in New York. With seeming lightning speed between introduction and implementation, and I watched some of this play out in real time on the APRL listserv, the New York State Bar Association has removed questions about mental health from its application entirely, with the expectation that students who need to get help when they are struggling will do so.

And that’s important. Yes, the current Wisconsin mental health questions also ask if applicants have ever cited physical illness as an excuse for poor academic or professional performance, but there’s no real stigma in answering that a heart attack or a broken leg took someone out of commission for awhile and caused grades to suffer. It’s another story if depression, anxiety, or another mental illness caused the exact same effect. This plays out in life generally—we tend to rally behind our friends with serious physical illnesses or injury; we don’t always know how to react when a friend tells us they’re attending day treatment for depression or taking meds for bipolar disorder.

In June at the State Bar Annual Meeting & Conference, I’ll be presenting on the topic of impaired practice, with Mary Spranger of the Wisconsin Lawyers Assistance Program (WisLAP). The session is still a work in progress, but I think ending the stigma will be part of it—our profession needs it, to be well and do well.