Selected Thoughts From the Select Committee Summary

Yesterday, the Select Committee to Investigate the January 6th Attack on the United States Capitol held its last hearing and released the introductory report to its findings. The full report will not be released until tomorrow, but the summary material (which is 154 pages in itself) provides a robust roadmap.

I watched some of yesterday’s hearing, and, I’m sure, like any other member of the ethics bar who may have been listening, my ears perked up when Rep. Lofgren outlined efforts by lawyers to influence witnesses and disrupt the investigation. (This is far from the most important information to be gleaned from the Committee’s work, but still.) Those efforts are described, beginning on page 93 of the summary.

The Select Committee has also received a range of evidence suggesting specific efforts to obstruct the Committee’s investigation. Much of this evidence is already known by the Department of Justice and by other prosecutorial authorities. For example:

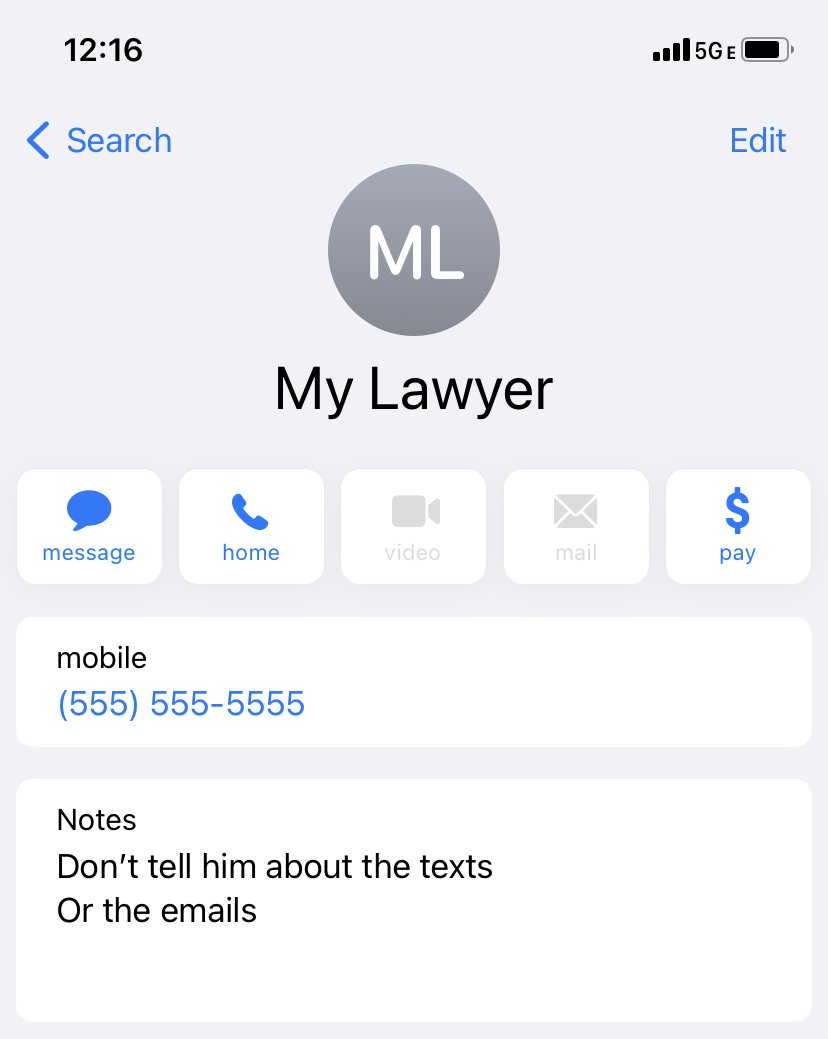

1. The Committee received testimony from a witness about her decision to terminate a lawyer who was receiving payments for the representation from a group allied with President Trump. Among other concerns expressed by the witness:

• The lawyer had advised the witness that the witness could, in certain circumstances, tell the Committee that she did not recall facts when she actually did recall them;

• During a break in the Select Committee’s interview, the witness expressed concerns to her lawyer that an aspect of her testimony was not truthful. The lawyer did not advise her to clarify the specific testimony that the witness believed was not complete and accurate, and instead conveyed that, “They don’t know what you know, [witness]. They don’t know that you can recall some of these things. So you saying ‘I don't recall’ is an entirely acceptable response to this.”;

• The lawyer instructed the client about a particular issue that would cast a bad light on President Trump: “No, no, no, no, no. We don’t want to go there. We don’t want to talk about that.”;

• The lawyer refused directions from the client not to share her testimony before the Committee with other lawyers representing other witnesses. The lawyer shared such information over the client’s objection;

• The lawyer refused directions from the client not to share information regarding her testimony with at least one and possibly more than one member of the press. The lawyer shared the information with the press over her objection.

• The lawyer did not disclose who was paying for the lawyers’ representation of the client, despite questions from the client seeking that information, and told her, “we’re not telling people where funding is coming from right now”;

• The client was offered potential employment that would make her “financially very comfortable” as the date of her testimony approached by entities apparently linked to Donald Trump and his associates. Such offers were withdrawn or did not materialize as reports of the content of her testimony circulated. The client believed this was an effort to impact her testimony.

Putting aside the political implications, the excerpt, above, is issue-spotting fodder for ethics nerds. (Fellow ethics nerd Kathleen Clark provided some solid analysis in a Twitter thread, and also concluded that the witness was likely Cassidy Hutchinson, and her lawyer Stefan Passantino, who among other things, was formerly an ethics lawyer in the Trump White House.)

With a hip of the hat to Prof. Clark, there are some takeaways for lawyers who are not inclined to interfere with Congressional investigations (or, really, be in a position to participate in a Congressional investigation in the first place).

For instance, I did get asked a couple of times yesterday whether a lawyer can accept payment from a third party who is unknown to the client. The answer is yes, but with caveats—SCR 20:1.8(f) allows a lawyer to accept compensation for representation from someone other than a client if:

(1) the client gives informed consent or the attorney is appointed at government expense; provided that no further consent or consultation need be given if the client has given consent pursuant to the terms of an agreement or policy requiring an organization or insurer to retain counsel on the client's behalf;

(2) there is no interference with the lawyer's independence of professional judgment or with the client-lawyer relationship; and

(3) information relating to representation of a client is protected as required by SCR 20:1.6.

(SCR 20:1.8(f)(1) differs from the Model Rule; the Model Rule only reads “(1) the client gives informed consent[.]” Still, Wisconsin’s expanded Rule makes some logical sense.)

In any case, it may be hard to reconcile informed consent from the client with anonymity of the payer, but it can be done. SCR 20:1.0(f) defines “informed consent” as “agreement by a person to a proposed course of conduct after the lawyer has communicated adequate information and explanation about the material risks of and reasonably available alternatives to the proposed course of conduct.” If you can communicate sufficient information about why the payer is anonymous, and reasonable alternatives (probably self-pay by the client), then such an arrangement is permissible.

More common, though, is the scenario in which a known third party is paying for legal services. This, of course, happens sometimes without our knowledge—perhaps your client has set up a GoFundMe, or received some funds from their family members or friends. That’s fine, and largely their business.

Where this can get a little dicey is when a parent funds a matter for their adult child—often, the parent wants to be directly involved in the matter, and sometimes even make decisions for their children. Absent informed consent of the client, that communication is not allowed—in those situations, tread carefully. I usually get my client’s written informed consent to discuss their matter with their parent—it seems to be a path of less resistance than trying to keep a wall between the two; still, you need to make it clear you represent the client, not the parent, and ultimately the client calls the shots and the parent isn’t to interfere.

Here, in the January 6 context, it’s clear that the payer (or someone aligned with the payer) was trying to call the shots. I hope it goes without saying that lawyers aren’t allowed to influence their clients’ testimony through offers of employment, or otherwise. Similarly, while “I don’t recall” is absolutely a valid answer to deposition questioning, it is only a valid answer if it’s true. Coaching your client to lie can implicate SCR 20:3.3(3) (candor toward the tribunal/offering evidence the lawyer knows to be false—depositions count), SCR 20:3.4(b) (counseling a witness to testify falsely), SCR 20:8.4(c) (conduct involving dishonesty), at least.

Beyond that, there was a big confidentiality breach here. It probably won’t get attention that the witness coaching and quid pro quo will (as it implicates a duty the lawyer owed to the client, not necessarily to the tribunal or the public). According to the summary, the lawyer was expressly told by their client not to share the client’s testimony to the Select Committee with other lawyers, for other witnesses; the lawyer shared the information anyway.

Model Rule 1.6 and its Wisconsin counterpart prohibit lawyers from revealing any information relating to representation of a client, absent informed consent, implied authorization, or certain exceptions not relevant to this matter. We don’t yet know why the witness didn’t want her lawyer to share information with others, but it doesn’t matter. Unless the contents of the witness testimony were such that revealing them was necessary to prevent death or serious bodily harm (and given the contents of the summary, that possibility is vanishingly small), the lawyer was way out of bounds here. It doesn’t matter if the lawyer believed this disclosure to be helpful to other witnesses, or to the cause generally; without the client’s consent, confidentiality is required.

On occasion, people do ask me to share reports, pleadings, or other information pertaining to representation of a client, so they can help their own clients in similar situations. In those cases, I am happy to help, but only if my client consents (and even then, my client may want certain things redacted, particularly if the document was not intended to be filed publicly).

Sometimes, clients want more privacy than would normally be expected—while generally, lawyers can discuss client matters within their own firm, in my line of work, it’s not entirely uncommon for my lawyer clients to not want me to talk about their matters with certain colleagues. To the extent that it’s possible to honor a request like that, I honor it; in cases where it just won’t work (i.e. if a client doesn’t want me to disclose their identity to anyone else at all, which would render conflict checking, billing, and mail processing nearly impossible) I advise the client I can’t reasonably comply with their wishes, and the client can decide whether to proceed with me or not.

Tantalizingly, the report also stated that “Further details regarding these instances will be available to the public when transcripts are released.” (p. 94.) It is my understanding that will happen tomorrow. Nothing like some light holiday reading, right?